Are the Thunder Cooking the Books For Shai Gilgeous-Alexander?

Conspiracies are contrived, data doesn’t lie, and this story is extraordinary

The Oklahoma City Thunder have stormed to the league’s best record (66-14) through incredible defensive ferocity (107.7 Def Rtg) and the magisterial play of Shai Gilgeous-Alexander. The simplest explanation of Gilgeous-Alexander’s game is that he is the league’s best scorer. His 32.7 points per game lead the league, and he gets there on a True Shooting percentage 10% better than the league average. That alone makes you elite, but it’s not the whole story. What takes him from the best high-volume scorer in the league to maybe the best offensive force is his ability to limit turnovers.

Among high-usage players (a usage above 28%) this season, Gilgeous-Alexander has the sixth-lowest turnovers per 100 possessions (3.4), and each player ahead of him owns a lower usage and assists per game figure. When you bump the usage threshold up to 30%, add a minimum of eight assists per 100 possessions, a maximum of 3.5 turnovers per 100 possessions (SGA is at 34.8%, 9.0, and 3.4), and expand it to the entirety of modern basketball, he enters rairfied air. There have only been six seasons since 1967-68 that reach the criteria; Michael Jordan in 1991-92, Jalen Brunson 2023-24, Kyrie Irving in 2021-22, Tracy McGrady in 2007-08, and Gilgeous-Alexander the past two seasons, and Gilgeous-Alexander’s seasons have the highest usage and True Shooting percentages by sizable margins.

While turnovers are routinely overlooked unless they prove costly, they’re one of the most consequential acts a player can make. A turnover guarantees zero points for an offensive possession; even a missed shot can lead to an offensive rebound, and the opposition scores at an elevated rate off of them. I can’t accurately ascribe a true point value to every turnover, but when you add the average point value per possessions with a shot (1.15) to the average point value of possession off of a turnover (1.22), you get a 2.37-point swing. That’s the equivalent of someone being a 79% 3-point shooter, and it’s one of the many reasons why advanced metrics love SGA.

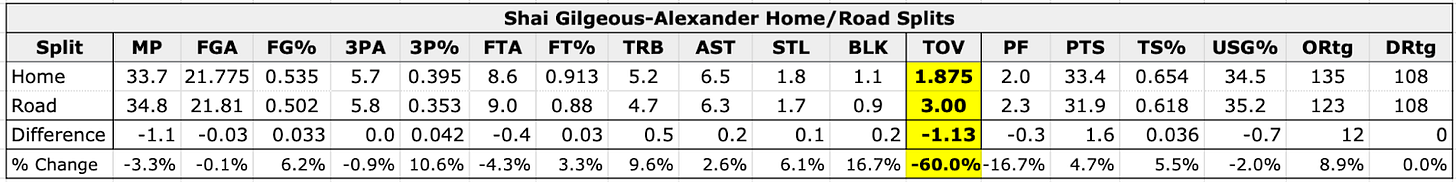

Shai Gilgeous-Alexander’s MVP case is pretty easy, despite Nikola Jokic owning the second-highest single-season offensive box plus/minus (OBPM) in history. He has the 14th-best OBPM ever and is propelling the Thunder to the second-highest net rating in history (+12.6). When a player has a historic season for a historic team, generally, they win MVP, but there is one mystery about his season that gave me some pause– his home/road turnover splits.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise to learn that players generally play better at home. If they didn’t, it’d be odd that teams have won about 54.4% of their home games this season. However, the degree to which Gilgeous-Alexander is better at home is bonkers.

Notice the highlighted section. At home, SGA turns the ball over 1.125 times less per game compared to on the road. For a very low turnover player, that represents a 60% change. The difference was so massive that it immediately caught my eye and sent me down a rabbit hole to try and explain why.

The first question I had to answer was: Is this normal? Do high-usage players generally see their turnovers drop substantially at home compared to on the road? To determine that, I took every player in both the top 50 in points scored at home and on the road, leaving me with a sample of 40 players. From there, I calculated their turnovers per 36 minutes to see just how much of an outlier Gilgeous-Alexander really is.

Note: I did this before the Thunder’s most recent home game, where Gilgeous-Alexander had only one turnover in 37 minutes. Also, the graphic above is per game and not per 36 minutes.

While many players see a significant reduction in their turnovers per 36 minutes at home, no one is on the same planet as Gilgeous-Alexander. Out of the overall sample of 40, the average player saw a reduction of 4.6% turnovers per 36 minutes at home, with 15 players seeing their turnovers per 36 minutes increase. The degree to which SGA has turned the ball over less at home is clearly out of the norm, but before I made any sweeping accusations, I had to see if the Thunder, as a team, were also outliers in this regard.

The Thunder do see their turnovers per game decline at home compared to on the road, but their 9.54% percent change is only the fourth best in the league. However, this only makes Gilgeous-Alexander’s home/road splits more interesting. The Thunder, as a team, have averaged 1.08 fewer turnovers at home compared to on the road, but SGA has averaged 1.13 fewer turnovers per game at home compared to on the road. Yes, if you exclude Gilgeous-Alexander’s turnovers, the rest of the Thunder have turned the ball over more at home than on the road. Now, that’s a tad misleading because at the time of the data collection, they had played more home games than road games, but if you normalize for minutes, it’s almost identical sans-SGA.

Needless to say, this bit of statistical evidence made me wonder, “Are the Thunder juicing SGA’s turnover numbers at home?” It’d be a savvy move to boost his MVP case. Fans generally don’t look all that hard at turnover numbers, but they’re incredibly powerful in all-in-one metrics that awards voters do utilize. And this wouldn’t be the first time something like this happened.

The NBA has a long history of teams pressuring scorers to inflate players’ stats. A since-deleted Deadspin article from 2009 recounts the practice in the '90s, and Pablo Torre Finds Out did a segment on the practice with the help of Tom Haberstroh. It’s not like anyone is making anything up; they are just entering the stats into the boxscore with rose colored glasses.

Unlike most stats, not all turnovers are black and white. If you get your pocket picked, throw the ball out of bounds, or travel, there’s not much a scorekeeper can do to bail you out. However, sometimes a turnover can straddle the line between a bad pass or a lost ball, and how the scorekeeper interprets fault goes a long way because the blame cannot be shared.

With so much smoke around Gilgeous-Alexander’s home/road turnover splits, I had to see if there was fire. So, I watched every Oklahoma City Thunder turnover at home this season. Through hundreds of video clips, I found only one clear example of turnover fraud (it was a clerical error for sure) and nine other instances where the scorekeeper decided to give Gilgeous-Alexander the benefit of the doubt.

These are my notes on all ten turnovers and then the video. I recommend reading the notes first so you know what to look for in the clips.

Video Notes

TOV 1: Clear scorekeeping error. Wallace doesn’t even make the pass but is assigned the turnover.

TOV 2: SGA makes a horrible pass. He short hops it to Wallace, who does his best to corral it but ultimately can’t and ends up being charged with the turnover. As you’ll see later, the scorekeeper can make some judgements in these situations.

TOV 3: Hartenstein is charged with an out-of-bounds turnover when that is literally impossible. The pass wasn’t great, but if the ball was out on the Thunder, the last guy to touch it had to be SGA.

TOV 4: Holmgren lost ball turnover, but it was a contested catch on a risky SGA pass. After watching hundreds of turnovers, I’ve seen this charged as a bad pass turnover numerous times.

TOV 5: Wiggins is charged with a bad pass turnover even though SGA, in an attempt to save the ball, throws it to the other team. Wiggins threw an awful pass, but SGA turned it over. This situation is similar to the Wallace out-of-bounds turnover and a future clip.

TOV 6: Clear turnover on Williams for a travel, but the errant pass forced him into that situation. As noted before, sometimes guys get punished for trying to make plays on poor passes, and sometimes they don’t.

TOV 7: Clear turnover on Hartenstein because he fumbled the ball, but I have seen turnovers charged to the passer on similar plays where no control is established.

TOV 8: Caruso bad pass turnover is a reverse of the Wiggins play. SGA throws a hospital ball into traffic that Caruso has to fight for to win, but it puts him in a situation where he is forced into a bad pass turnover. As mentioned before, when that happened to SGA, he got the benefit of the doubt.

TOV 9: Williams is charged with a bad pass turnover, and it is a bad pass, but SGA gets his hands on the ball before it is wrestled away. As we’ve seen before, sometimes those are charged as lost ball turnovers.

TOV 10: Big Williams lost ball turnover. It is similar to the Chet one, where SGA makes a pass requiring a tough catch. Williams almost corrals it but loses control at the end. Could easily have been given as a bad pass turnover.

After hours of data research, I thought I had stumbled onto a grand conspiracy, but the hard evidence provided little. Yes, one turnover was clearly misappropriated, but in the end, most of these decisions were marginal. While it’s clear that Gilgeous-Alexander was given the benefit of the doubt when possible, it only amounted to maybe seven, eight, or nine fewer turnovers. But then something dawned on me: maybe seven, eight, or nine fewer turnovers is all that it takes to look like an outlier.

Using the turnovers per 36 leaderboard from before, which made Gilgeous-Alexander look like an alien at home, I added nine additional home turnovers to his ledger to see what type of difference it would make.

I mean, that’s it. That pretty much explains everything. Sure, Gilgeous-Alexander still leads this leaderboard, but it’s by a hair and completely within the norm. After all of this, it’s safe to say the Oklahoma City Thunder scorekeepers have probably helped to deflate Gilgeous-Alexander’s home turnover numbers. It’s also safe to say that what they’re doing isn’t a grand conspiracy, but rather, it’s the NBA’s time-honored tradition of supporting your superstar. However, the real story is just how comically good Shai Gilgeous-Alexander is, particularly at home. He’s having one of the best seasons of the past 25 years, and his ability to limit turnovers, with the tiniest help from his friends, is a big reason why.

For any inquiries about work, discussion, and the like, you can email me at nevin.l.brown@gmail.com.

Great breakdown! Must have taken hours to track down all those turnovers.

Now THIS is basketball journalism

Turnovers and steals are some of the easiest things to (even subconsciously as a scorekeeper) favor home guys on, because you can’t say with 100% certainty at times who caused them